10 Greatest Lawyers of All Time—That Every Future Law Student Should Know

- Dale Park

- 3 hours ago

- 13 min read

The law is not merely a collection of rules or courtroom procedures—it is a disciplined search for truth, a framework for justice, and a foundation for maintaining a productive and harmonious society. At its best, law provides the structure that allows free people, markets, and institutions to function with fairness, predictability, and mutual trust. For students drawn to debate, history, politics, and rigorous reasoning, the study of law offers one of the most intellectually demanding and socially consequential paths available.

This article explores ten of the greatest lawyers of all time. These figures did not simply practice law; they helped refine legal principles, strengthened institutions, defended fundamental rights, and shaped how societies reason about justice and responsibility. From courtroom masters to constitutional thinkers, their lives demonstrate why law remains indispensable to the stability and progress of civilizations.

For ambitious high school students considering summer law courses or research internships, these lawyers offer more than inspiration. They exemplify how careful reasoning, persuasive communication, ethical judgment, and respect for legal institutions can define extraordinary careers—and contribute meaningfully to the world they serve.

Thomas More (1478–1535)

Thomas More stands as one of the earliest and most morally complex figures in legal history. Born in London in 1478, More was trained as a lawyer at Lincoln’s Inn and rose to become one of the most respected jurists in England. His legal career culminated in his appointment as Lord Chancellor under King Henry VIII, the highest judicial office in the realm.

Alongside his distinguished legal career, More was also a profound legal philosopher. His most famous work, Utopia (1516)—a term he coined, explores an imagined society governed by reason, shared responsibility, and laws designed to serve the common good rather than elite interests. Although often read as a work of political philosophy, Utopia is deeply legal in nature, raising enduring questions about justice, property, punishment, and the relationship between law and morality.

More’s greatness as a lawyer lies in his principled understanding of law as a moral enterprise. He believed that law existed to restrain arbitrary power, even when that power belonged to the sovereign. This belief ultimately cost him his life. When Henry VIII demanded recognition as Supreme Head of the Church of England, More refused to endorse the break with Rome, arguing that the king’s command violated both conscience and law.

His execution in 1535 made him a symbol of legal integrity: a lawyer who placed the rule of law above personal advancement and even survival. For students of law, More represents an enduring lesson—that moral courage is an attribute essential for those who wish to devote their life to justice.

William Blackstone (1723–1780)

If Thomas More embodied moral resistance to power, William Blackstone provided the intellectual architecture of modern common law. Born in London in 1723, Blackstone was a barrister, judge, and above all a legal scholar whose influence extends far beyond his lifetime.

Blackstone’s monumental Commentaries on the Laws of England systematized centuries of English common law into a coherent and accessible framework. Before Blackstone, the law was largely understood through scattered cases and arcane traditions. His work transformed it into an intelligible canon of principles that could be taught, studied, and applied consistently.

The Commentaries profoundly shaped legal education in Britain and, even more significantly, in the American colonies and early United States. Many of the Founding Fathers—including lawyers such as John Adams and Thomas Jefferson—were deeply influenced by Blackstone’s ideas. His articulation of individual rights, private property, and legal process became foundational to Anglo-American legal culture.

Blackstone’s greatness lies in his ability to make law systematic without stripping it of moral purpose. He demonstrated that legal clarity itself is an essential form of justice.

John Adams (1735–1826)

John Adams is often remembered as a revolutionary statesman and the second President of the United States, but at his core he was a lawyer of exceptional rigor, discipline, and principle. Born in 1735 in Massachusetts and trained at Harvard, Adams developed a deep respect for the common law and a firm belief that liberty could survive only where law restrained both rulers and crowds. His legal mind was shaped not by ideology alone, but by an unyielding commitment to procedural fairness and institutional integrity.

Adams’s defining legal moment came in 1770, when he agreed to defend the British soldiers charged in the Boston Massacre. In an atmosphere of public fury and political danger, Adams insisted that justice demanded fair trials even for enemies of the people. By securing acquittals for most of the accused through careful evidence, witness examination, and adherence to legal standards, Adams demonstrated that the rule of law must stand above passion if society is to remain free. He later reflected that this defense was one of the most important services he ever rendered to his country.

This episode illustrates Adams’s central legal insight: that justice is not measured by outcomes that satisfy popular sentiment, but by fidelity to principle. By upholding due process at a moment when it was most vulnerable, Adams reinforced public confidence in law as a neutral arbiter rather than a tool of vengeance. In doing so, he showed how legal integrity serves as a stabilizing force, preserving social order even amid revolutionary change.

Adams carried this philosophy into the design of American constitutional government. He was instrumental in shaping the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, which became a model for written constitutions, separation of powers, and an independent judiciary. His insistence on checks and balances reflected a lawyer’s understanding of human fallibility and the necessity of institutional restraint. Law, for Adams, was not an obstacle to liberty but its strongest safeguard.

John Adams’s greatness lies in his demonstration that societies endure through steadfast adherence to legal principle. By elevating justice above faction and law above passion, he exemplified how disciplined legal reasoning can preserve freedom, legitimacy, and social cohesion across generations.

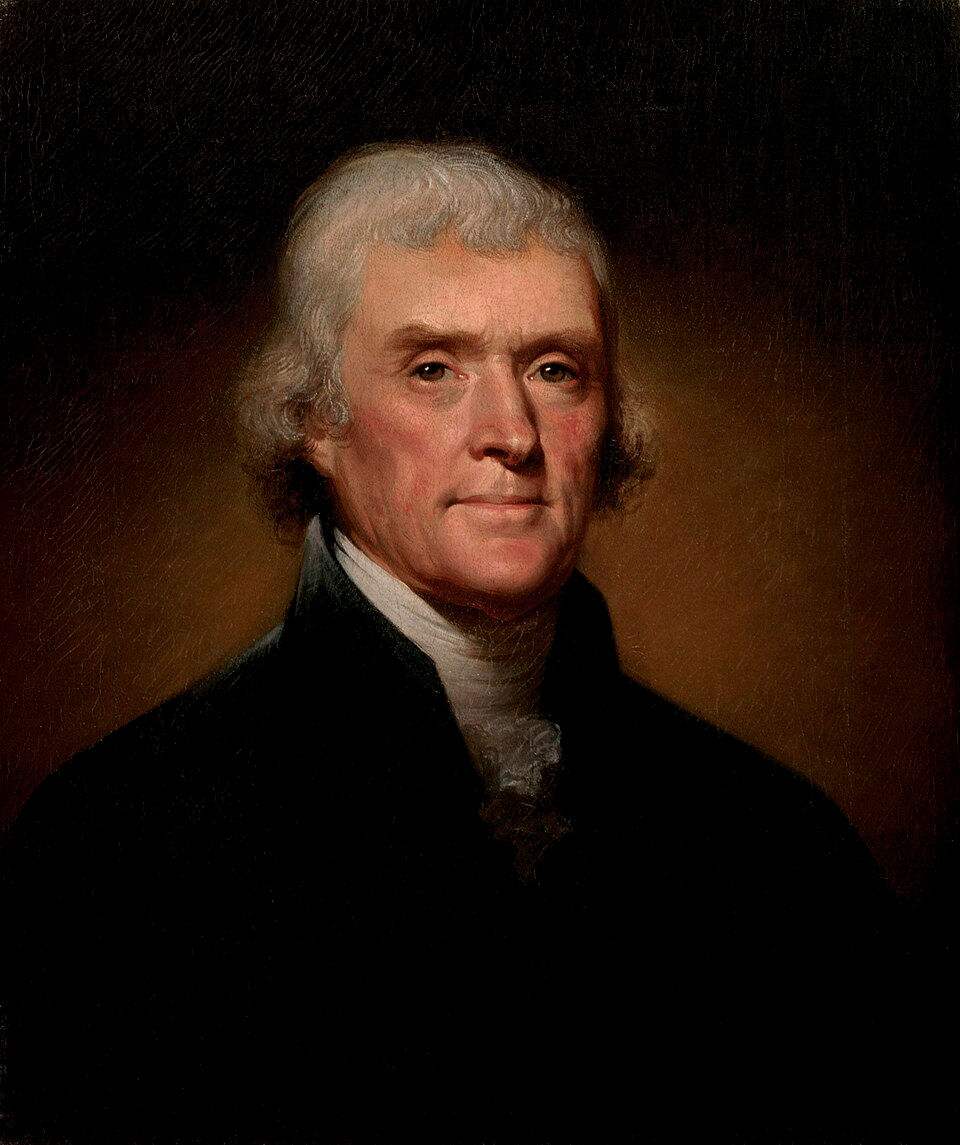

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826)

Thomas Jefferson’s legal greatness lies in his role as a principal legal architect of the American republic. Born in 1743 in Virginia and trained as a lawyer under George Wythe, Jefferson developed a sophisticated command of common law, natural law, and Enlightenment political theory. Among the thinkers who most deeply shaped his legal philosophy was John Locke, whose theories of natural rights, consent, and lawful resistance provided Jefferson with a coherent framework for grounding political authority in law rather than tradition or force.

Jefferson’s most consequential legal achievement—the drafting of the Declaration of Independence—reflects Locke’s influence with remarkable clarity. The Declaration translates Lockean principles into juridical language, asserting that individuals possess inherent rights, that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed,” and that persistent violations of those rights justify legal separation. Jefferson did not merely echo Locke; he refined and operationalized Lockean theory, transforming abstract philosophy into a legal instrument capable of legitimizing revolution before both domestic and international audiences.

Beyond the Declaration, Jefferson applied these same principles to concrete legal reform. In Virginia, he worked systematically to align statutory law with natural-rights theory, dismantling inherited legal privileges and emphasizing equality before the law. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom stands as a direct application of Lockean ideas about conscience and limited government, establishing religious belief as a domain beyond the reach of civil authority and embedding freedom of thought as a legally protected right.

Jefferson’s broader constitutional vision—articulated in his legislative work, executive practice, and extensive correspondence—reinforced a Lockean emphasis on limited power, decentralization, and vigilance against concentrated authority. He understood law as a safeguard for liberty, not merely a tool of governance, and insisted that legitimacy depends on adherence to clearly defined legal principles rather than expedience or tradition.

Thomas Jefferson’s greatness as a lawyer rests on his ability to translate philosophical insight into enduring legal form. By fusing John Locke’s natural-rights theory with practical legal craftsmanship, Jefferson helped create a constitutional framework that grounded political authority in reason, consent, and law—principles that continue to define the legal foundations of free societies around the world today.

Clarence Darrow (1857–1938)

Clarence Darrow is widely regarded as the greatest courtroom lawyer in American history. Born in 1857 in Ohio, Darrow became renowned for defending society’s most reviled and vulnerable defendants, guided by a profound skepticism of moral absolutism and a lifelong opposition to cruelty, especially the death penalty. At a time when public opinion often demanded punishment rather than understanding, Darrow consistently placed human complexity at the center of the law.

Darrow’s advocacy was rooted in empathy, psychological insight, and intellectual depth. He rejected simplistic notions of free will and moral blame, arguing instead that crime and wrongdoing were shaped by heredity, environment, and social conditions. This perspective allowed him to reframe criminal trials away from vengeance and toward understanding, compelling judges and juries to confront the human causes behind unlawful acts rather than merely their consequences.

This approach reached its apex in the 1924 Leopold and Loeb murder case. Facing overwhelming evidence of guilt, Darrow abandoned the hope of acquittal and instead delivered a twelve-hour sentencing argument against the death penalty—one of the most influential legal orations ever given. Drawing on philosophy, science, psychology, and moral reasoning, he persuaded the judge to spare the defendants’ lives, demonstrating how law could resist public fury and affirm human dignity even in the most disturbing cases.

Darrow’s influence extended beyond criminal defense. In the 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial, he transformed a local prosecution over the teaching of evolution into a national confrontation between scientific inquiry and religious fundamentalism. Through his cross-examination of William Jennings Bryan, Darrow exposed the intellectual fragility of literalist interpretations of scripture, defending freedom of thought and education against ideological constraint. Though Scopes was technically convicted, Darrow won the larger cultural battle by reshaping public discourse.

Clarence Darrow’s greatness lies in his ability to use the courtroom as a forum for moral reasoning without abandoning legal rigor. Through unmatched rhetorical power, psychological insight, and moral courage, he demonstrated that the highest calling of advocacy is not merely to win cases, but to expand society’s understanding of justice itself.

Melvin Belli (1907–1996)

Melvin Belli, born in 1907 in California, revolutionized personal injury law and modern trial advocacy. Widely known as the “King of Torts,” Belli fundamentally changed how civil damages were argued, proven, and understood by juries at a time when injury cases were often treated as abstract disputes over liability and compensation.

Belli’s greatness lay in his ability to make invisible harm visible. Before his rise, personal injury trials relied heavily on technical testimony and legal formalism that failed to convey the real consequences of injury. Belli pioneered the systematic use of demonstrative evidence—medical illustrations, physical exhibits, timelines, and in-court demonstrations—to translate pain, disability, and future loss into concrete, comprehensible terms. By showing jurors what an injury meant in lived experience, he transformed damages from speculative numbers into moral and factual realities.

Equally important was Belli’s command of narrative and psychology. He understood that jurors needed a coherent story connecting negligence to human consequence. His courtroom presentations integrated expert testimony, visual evidence, and emotional resonance without abandoning factual rigor. Though critics dismissed his approach as theatrical, Belli maintained that clarity and persuasion were not embellishments but necessities when justice depended on jurors grasping the full weight of harm.

Belli’s influence extended far beyond his own cases. Techniques he normalized—visual aids, demonstrative exhibits, structured storytelling, and damages-focused advocacy—are now standard features of civil trials worldwide. Entire fields of trial consulting, litigation graphics, and courtroom presentation trace their origins to methods Belli refined decades earlier.

Melvin Belli’s legacy rests on his permanent reshaping of civil litigation. By expanding how lawyers could prove and communicate injury, he elevated the jury’s role in assessing harm and established persuasive clarity as a central pillar of effective and just advocacy.

Lionel Luckhoo (1914–1997)

Lionel Luckhoo, born in 1914 in British Guyana, is widely regarded as one of the most successful criminal defense lawyers in history. He earned international recognition for securing more than 240 acquittals in murder trials—an unmatched record that led Guinness World Records to recognize him as the world’s most successful lawyer. Practicing across the Caribbean, Africa, and the United Kingdom, Luckhoo built his reputation in jurisdictions where capital punishment was frequently imposed and the margin for error was often fatal.

Luckhoo’s extraordinary success stemmed from his meticulous command of evidence and procedure. He was renowned for dismantling prosecution cases by exposing investigative gaps, unreliable witness testimony, and procedural violations—often in legal systems that assumed guilt and placed heavy burdens on the accused. His preparation was exhaustive: he reconstructed timelines, tested forensic assumptions, and scrutinized confessions for coercion or inconsistency, frequently revealing flaws that juries and judges could not ignore.

Equally important was Luckhoo’s disciplined courtroom style. He avoided theatrics, relying instead on calm logic, precision, and credibility. In cases where public sentiment and political pressure favored conviction, Luckhoo focused relentlessly on reasonable doubt, forcing courts to confront the weakness of evidence rather than the gravity of the accusation. His advocacy saved hundreds of defendants from the gallows and set higher standards for criminal defense practice in colonial and post-colonial legal systems.

Beyond individual cases, Luckhoo helped professionalize criminal defense advocacy in regions where defendants’ rights were often underdeveloped. His success demonstrated that rigorous defense lawyering could function as a meaningful check on state power, even in hostile or resource-poor environments.

Lionel Luckhoo’s greatness lies in the scale and consistency of his results. Through disciplined analysis, procedural mastery, and unwavering commitment to due process, he showed that effective advocacy can prevail even where the stakes are life and death, leaving a legacy defined not by fame, but by lives saved and justice enforced.

Gerry Spence (1929–2025)

Gerry Spence, born in 1929 in Wyoming, is renowned for one of the most extraordinary jury trial records in American legal history. Over decades of courtroom practice, Spence claimed never to have lost a criminal jury trial and never to have lost a civil jury trial as a plaintiff—an achievement that placed him among the most feared and respected trial lawyers in the country. His victories included high-stakes cases against powerful corporate and government defendants, where he repeatedly prevailed despite overwhelming resources aligned against him.

Spence’s effectiveness stemmed from his radical departure from traditional legal formalism. He rejected technical jargon, scripted performances, and detached professionalism, choosing instead to speak to jurors in plain language grounded in shared moral intuition. He treated jurors not as passive recipients of information but as ethical decision-makers. By openly expressing doubt, emotion, and even vulnerability, Spence established credibility and trust—often disarming opponents whose arguments relied on authority rather than persuasion.

Central to Spence’s approach was his belief that trials are fundamentally moral narratives, not merely factual disputes. He excelled at framing cases around fairness, responsibility, and abuse of power, enabling jurors to understand complex legal issues through clear human stories. This method proved especially effective in cases involving individuals confronting institutions, where Spence consistently transformed imbalance into moral urgency.

Beyond the courtroom, Spence profoundly shaped legal culture through his writing and teaching. His books—including the widely read How to Argue and Win Every Time—brought the principles of persuasion, authenticity, and ethical advocacy to a broad audience well beyond the legal profession. He also founded the Trial Lawyers College, an unconventional training institution devoted to teaching lawyers to advocate with empathy, self-awareness, and integrity rather than rote technique.

Gerry Spence’s greatness lies in his demonstrated ability to win juries by earning their trust. Through both his trial record and his enduring influence as an author and teacher, he showed that the most powerful advocacy is rooted not in cleverness or intimidation, but in honesty, moral clarity, and genuine human connection.

F. Lee Bailey (1933–2021)

F. Lee Bailey is widely regarded as one of the most formidable defense attorneys of the twentieth century. Born in 1933, Bailey rose to prominence during the rise of televised trials, becoming a household name through his representation of defendants in some of the most consequential criminal cases in American history, including those of Sam Sheppard, Patty Hearst, and O.J. Simpson.

Bailey’s greatness lay above all in his mastery of cross-examination. He had an exceptional ability to dismantle prosecution witnesses by exposing inconsistencies, bias, and overconfidence, often without appearing aggressive or theatrical. In the Sheppard case, his relentless scrutiny of police conduct helped reveal investigative failures that led to Sheppard’s eventual acquittal after years of imprisonment. During the O.J. Simpson trial, Bailey’s probing of forensic evidence and law enforcement credibility—particularly his questioning surrounding evidence handling—played a central role in creating reasonable doubt.

Equally important was Bailey’s strategic command of narrative. He understood that juries do not decide cases on facts alone, but on how those facts are framed. Bailey integrated procedural precision, evidentiary detail, and psychological insight to recast complex cases into coherent and persuasive stories favoring the defense. His ability to anticipate prosecutorial moves and exploit procedural missteps made him especially dangerous to face in court.

Although his later career was marked by controversy, Bailey’s influence on criminal defense law remains profound. He redefined the role of the defense attorney as an aggressive guardian of due process, demonstrating how rigorous cross-examination, evidentiary fluency, and courtroom strategy could alter the trajectory of even the most seemingly unwinnable cases. His legacy endures as a benchmark for excellence in trial advocacy.

Clarence Thomas (1948– )

Born in 1948 in Georgia, Clarence Thomas rose from poverty to become the greatest justice in the history of the United States Supreme Court. His judicial career is defined by an uncompromising commitment to constitutional originalism and a rigorous reliance on historical analysis. Across decades on the Court, Thomas has consistently argued that the Constitution derives its legitimacy from its fixed meaning, not from the preferences of judges or shifting political winds.

Thomas’s greatness lies in his intellectual consistency and methodological discipline. He rejects the idea that constitutional meaning evolves through judicial interpretation, insisting instead that judges are bound by the Constitution’s text as it was publicly understood at the time of its adoption. By anchoring constitutional law in history rather than discretion, Thomas has preserved the rule of law and protected democratic self-government—ensuring that fundamental change occurs through amendment and legislation, not judicial invention.

Throughout his career, Thomas has returned relentlessly to first principles. His opinions reexamine foundational assumptions about federal power, administrative authority, individual rights, and the separation of powers. In areas ranging from commerce and federalism to free speech and criminal procedure, he has pressed the Court to confront whether modern doctrines are faithful to the Constitution’s original structure. Even when writing alone, his reasoning has often laid the groundwork for later shifts in constitutional law, demonstrating how ideas, patiently argued, can reshape institutions over time.

In an era marked by political polarization and institutional distrust, Thomas’s jurisprudence emphasizes continuity, limits, and restraint. By insisting that judges are guardians rather than authors of the Constitution, he has worked to preserve the stability of American constitutional government amid increasing social and political division.

Clarence Thomas’s legacy rests not on rhetoric or popularity, but on the enduring influence of disciplined legal reasoning. Through his steadfast commitment to historical meaning and constitutional boundaries, he has demonstrated how principled interpretation can serve as a stabilizing force—helping to preserve the constitutional framework upon which the United States depends.

Conclusion: Why Studying Law Early Matters

The lawyers featured in this article share little in common on the surface. They lived in different centuries, practiced in different legal systems, and even held sharply contrasting political views. Yet they are united by one essential trait: each understood that law is an intellectual discipline capable of shaping societies, restraining power for the common good, and defending human dignity.

For students with strong analytical skills, curiosity about justice, and an interest in history or public affairs, early exposure to legal thinking can be transformative. Studying law develops precision in reasoning, clarity in writing, and confidence in argument—skills that elite universities and top firms actively seek, and whose benefits extend far beyond the courtroom.

World Scholars Academy’s Law courses and Law research internships are designed for motivated students ages 12-18 who want to engage with these ideas at a serious pre-collegiate level. Through intensive seminars, research-focused coursework, and close mentorship, students explore legal philosophy, landmark cases, and real-world legal problems while building the intellectual independence required for elite university study.

Whether your ambition is to become a lawyer, policymaker, academic, or informed global citizen, studying law now can provide a powerful foundation. The great lawyers of history began as students who learned to think rigorously, argue carefully, and question consensus. The same journey can begin much earlier than you might expect.

For students who are serious about exploring this path, we recommend reading So You Want to Be a Lawyer? 10 Essential Skills for Success, which breaks down the core intellectual and personal skills required to thrive in legal study and practice. This article complements the historical examples above by showing how aspiring lawyers today can begin developing those skills early.